- The Breakdown

- Posts

- 🟪 Banking is a patchwork of metaphorical messages

🟪 Banking is a patchwork of metaphorical messages

Less complicated, please

Banking is a patchwork of metaphorical messages

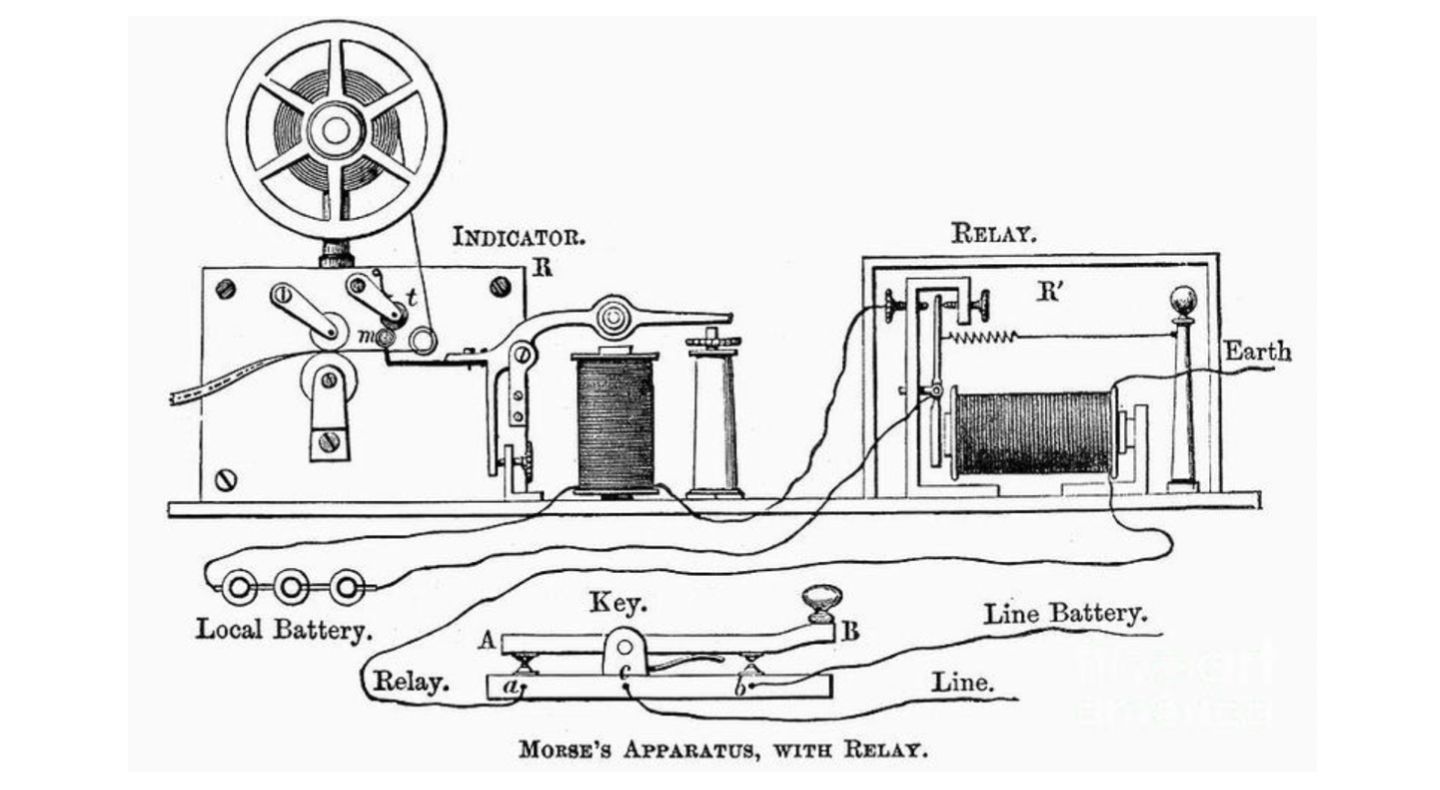

When the telegraph was introduced, the idea of encoding information within currents of electricity was so foreign to people that it could only be explained in more familiar language: Telegraphs were presented as a way to send a message over a wire.

As documented in an 1873 edition of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, this caused some confusion:

One woman refused to believe that a telegram she’d received was from her son because it wasn’t in his handwriting.

Another brought a batch of homemade sauerkraut to the local telegraph office and asked that it be sent to family in another city.

A child, hearing that dispatches were being sent by telegraph, “watched a long time in hopes of seeing some of them darting along the wires.”

And a man in Bangor, ME refused to believe his message had been sent because the telegraph operator had stuck it on a hook on the wall with all the others: “‘Ain’t you going to send that dispatch?’ The operator politely informed him that he had sent it. ‘No, yer ain’t,’ replied the indignant man; ‘There it is now on the hook.’”

Harper’s reported these incidents not with derision, but understanding: “So far as the exact use of language was concerned the man was right.”

Customers were promised the messages they brought to a telegraph office would be “sent,” and they were right to suspect they weren’t.

The Harper’s article, which begins on page 332 of that month’s edition, spends several thousand words explaining to its readers how both electricity and telegraphs work (oh, to have the attention span of a 19th century magazine reader!).

The author concludes by confirming those customers’ suspicions that nothing is actually “sent” along a copper wire.

This inexact language was central to the confusion: “The difficulty of forming a clear conception of the subject is increased by the fact that while we have to deal with novel and strange facts, we have also to use old words in novel and inconsistent senses.”

To make a new technology comprehensible, people typically use words that are only “somewhat analogous” in nature, and which “call up in the mind conceptions quite inadequate to the new fact.”

The idea that a message is “sent” along a wire is one of these inadequate analogies.

Harper’s explains why using old words for new facts can cause problems: “When it is said that a current of electricity flows along the wire, that the wire or the current carries a message, the speaker takes language universally understood, relating to a fluid moving from one place to another, and a parcel or letter transported from place to place. He does not, however, mean that there is any stream flowing, or any thing [sic] whatever transported.”

Not even an electrical current.

The Harper’s author defines "electrical current” more precisely as a “vibratory action and reaction,” and explains that it doesn’t travel down a wire, but happens everywhere all at once: “An excitement of force taking place throughout the whole line if at all, ceasing every where if the line is broken at any point whatever.”

In other words, even “electrical current” is a metaphor for what’s being “sent” down a telegraph wire.

The scientific understanding of electricity may have advanced since 1873, I'm not sure (everything I know about electricity I learned from this long, amazingly well-written article).

But the big takeaway stands: “We are not to conceive of the electricity as carrying the message that we write, but rather as enabling the operator at the other end of the line to write a similar one.”

This is how banks work, too!

When we pay someone by wire transfer, we typically think we are “sending” money from our bank to theirs.

But, unless you’re sending an envelope full of cash, that, too, is a metaphor — because money cannot be sent over a wire any more than homemade sauerkraut can.

Instead, the only thing sent between banks is messages (also a metaphor!).

You message a bank your payment instructions, your bank messages the recipient's bank, both banks message the Federal Reserve, and everyone updates their spreadsheets accordingly.

The global banking system consists of thousands of siloed spreadsheets, many still running on ancient COBOL mainframes, kept in sync by millions of instructions exchanged between banks every day.

“Sending money” is just a metaphor for the process of adding a number to one of those spreadsheets and subtracting the same number from another.

It’s kind of unsettling when you stop to think about it — like looking down at the suspension bridge you’re crossing and discovering it’s cobbled together from irregular planks of wood held in place by frayed bits of rope.

Surely there’s a less metaphorical way to move money than all this sending of messages?

One of the chief message senders, SWIFT, seems to think so.

This week, the all-important payments cooperative announced the development of a “blockchain-based shared ledger” that will enable its many member banks to make cross-border transactions with stablecoins.

This would vastly simplify things because stablecoins exist on a shared ledger that everyone can update themselves.

Instead of syncing thousands of siloed ledgers with millions of messages, banks could all update a single ledger — or their customers could do it themselves.

With stablecoins, it still feels like you’re sending money from one place to another.

But, being on a blockchain, it’s much clearer what we’re actually doing: updating ledgers.

Most people won’t want to do that themselves, so most people will probably still pay banks to do it for them.

But they’ll pay less and it will happen faster because cutting out all those messages should make “moving” money far less complicated.

And less metaphorical, too.

Brought to you by:

Grayscale is excited to announce the launch of Grayscale CoinDesk Crypto 5 ETF (ticker: GDLC) — the first crypto exchange-traded product in the U.S offering investors access to the market cap-weighted performance of the five largest and most liquid crypto assets1 , covering 90% of the crypto market’s capitalization2 .

Grayscale CoinDesk Crypto 5 ETF (“GDLC” or the “Fund”), an exchange traded product, is not registered under the Investment Company Act of 1940 (or the ’40 Act) and therefore is not subject to the same regulations and protections as 1940 Act registered ETFs and mutual funds. Investing involves risk, including possible loss of principal. An investment in GDLC is subject to a high degree of risk and volatility. GDLC is not suitable for an investor that cannot afford the loss of the entire investment. An investment in the Fund is not a direct investment in any cryptocurrency.

Grayscale CoinDesk Crypto 5 ETF has filed a registration statement (including a prospectus) with the SEC for the offering to which this communication relates. Before you invest, you should read the prospectus in that registration statement and other documents GDLC has filed with the SEC for more complete information about GDLC and this offering. You may get these documents for free by visiting EDGAR on the SEC Web site at www.sec.gov. Alternatively, GDLC or any authorized participant will arrange to send you the prospectus after filing if you request it by calling (833)903-2211 or by contacting Foreside Fund Services, LLC, Three Canal Plaza, Suite 100, Portland, Maine 04101.

Foreside Fund Services, LLC is the Marketing Agent and Grayscale Investments Sponsors, LLC is the sponsor of GDLC.

By Ben Strack |

By Boccaccio |

By Ben Strack |

Sponsored Content |

Crypto is changing TradFi derivatives and rate markets as we know them.

DAS: London will feature all the builders driving this change.

Get your ticket today with promo code: BREAKDOWNNL

📅 October 13-15 | London

Tell your friends, rack up rewards! 🎉

Some market insights are just too good to not share. Use the Breakdown referral program and snag rewards while you’re at it:

1 Grayscale and CoinDesk, as of 8/29/2025. Largest and most liquid assets reflect eligibility for U.S. exchange and custody accessibility and U.S. dollar or U.S. dollar-related trading pairs. Exclusions include stablecoins, memecoins, gas tokens, privacy tokens, wrapped tokens, staked assets, or pegged assets. Largest is defined by circulating supply market capitalization, and most liquid is defined by 90-day median daily valued traded.

2 CoinDesk as of 08/31/2025, based on the crypto market ’s total investable universe.