- The Breakdown

- Posts

- 🟪 Friday charts

🟪 Friday charts

AI will reallocate our talents

Friday charts: AI will reallocate our talents

At some point I noticed that the new joiners on the trading floor I worked on in 2007 seemed increasingly overqualified for their jobs.

One had just graduated from Cambridge University with a doctoral degree in Chemistry. His job at the bank was making PowerPoint slideshows about structured derivatives to present to clients.

Another was a nuclear physicist, whose previous job was helping to ensure that nuclear weapons in Russia did not accidentally explode. For us, he traded options.

This misallocation of human capital was a sign of an unbalanced economy: People who should have been making unique contributions to the world were instead doing things at banks that made little difference to anyone outside banking.

It was also a warning sign that investment banking, bloated with misallocated talent, was about to topple over.

The one good thing that can be said about the financial crisis that soon followed was that it released a lot of those smart people back into the broader economy, where many of them found far more productive things to do.

As painful as that process was for the individuals involved (I speak from experience), I imagine that reallocation of human capital must have raised productivity in the economy at large.

That has been the historical norm, at least.

In the 19th century, as farming got more productive thanks to innovations like crop rotation and artificial fertilizers, labor was freed up to work in factories. Some of those factories made things like steel plows that made farming even more productive, freeing up more labor to make more things in factories — a virtuous cycle of rising productivity.

A more recent example is the washing machine, which Hans Rosling says is one of history’s most liberating technologies. Rosling recounts how his mother’s first washing machine gave her time to read books to him — setting him on a path to become an influential physician, statistician and “edutainer.”

Others used their newfound free time to enter the labor force: In the United States, the labor-force participation rate for women rose from 32% in 1950 to 57% now.

Almost anything is more productive than hand-washing clothes, so the reallocation of that human capital became a decades-long tailwind for the world economy.

The question to ask ourselves now is whether AI will be the knowledge economy’s washing machine.

Much of what software engineers do at work today is nearly as routine as doing laundry — boilerplate code, debugging, repetitive testing. So it stands to reason that if AI starts doing those things for them, engineers will be freed to do something more valuable.

The historical logic seems sound. But some economists worry this time will be different.

Economist Adair Turner, for example, warns that “super rapid technological growth is bound to result in a proliferation of low productivity jobs, zero-sum competitive activities, and increases in real consumption which never show up in GDP statistics.”

The people whom washing machines released into the job market did positive-sum things like teaching, nursing and sales. WhereasTurner fears the people released by AI will do zero-sum things like play video games and bet on sports.

This, he thinks, is why productivity gains from the internet era have been so underwhelming: “Radical automation may eventually reduce towards zero the number of people involved in those economic activities essential to produce the goods and services which support human welfare.”

Others are more optimistic.

Economist David Autor thinks we’re too worried about the jobs we might lose and not hopeful enough about the productivity we might gain: “Focusing only on what is lost misses a central economic mechanism by which automation affects the demand for labor: raising the value of the tasks that workers uniquely supply.”

Autor expects that AI, like farming and washing machines, will make humans more productive by freeing them from routine tasks: “the interplay between machine and human comparative advantage allows computers to substitute for workers in performing routine, codifiable tasks while amplifying the comparative advantage of workers in supplying problem-solving skills, adaptability, and creativity.”

Few seem to share Autor’s optimism.

Instead, there’s a growing consensus that AI will soon become so capable it replaces whole categories of jobs, starting with software engineering.

If software engineers were suddenly displaced en masse, could their talents be productively reallocated elsewhere?

It’s never happened before, so there’s no economic literature to cite. But even in that extreme scenario I see reasons for optimism — because it’s hard for me to imagine that human capital is already perfectly allocated to its most productive uses.

People smart enough to be software engineers might be more productive as hardware engineers, for example.

I imagine that could be a net positive: Building, say, machines that extract carbon dioxide from the atmosphere would be more societally beneficial than writing code that extracts yet another advertising dollar from your Instagram feed.

Similarly, business majors might be liberated from a future of project management and train to fill the chronic shortage of electricians instead.

Newsletter writers could become more societally productive by doing, well…pretty much anything else!

(Video games and sports betting will be a sore temptation, however.)

I’m oversimplifying, of course. Most people can’t switch careers on a dime.

But if AI causes more people to study, say, materials science instead of computer science, that could make the economy more productive over time.

However capable AI proves, history (and the bank I used to work at) suggests human talent will find its way to harder, more important problems.

Let’s check the charts.

Compounding productivity:

As recently as the 1960s, South Korea and Ghana had the same GDP per capita. The divergence since then is the result of productivity rising in one economy and staying stagnant in the other.

Doing more with less:

It’s almost a cliche to note that the advanced economies went from 60%+ employment in agriculture to near zero without a rise in unemployment. But the chart is still pretty amazing.

Just doing less:

Rising productivity also means people spend ever more time on leisure and discretionary pursuits and less time working.

The long productivity boom:

The corollary to falling agricultural employment is rising agricultural productivity. Sweden is cited here because they kept the best data.

Rising abundance:

Human Progress defines “abundance” as hourly earnings less CPI. On that measure, the last 20 years have been pretty good.

Especially for blue collar work:

The way Human Progress measures it, blue-collar workers have done better than average over the past two decades.

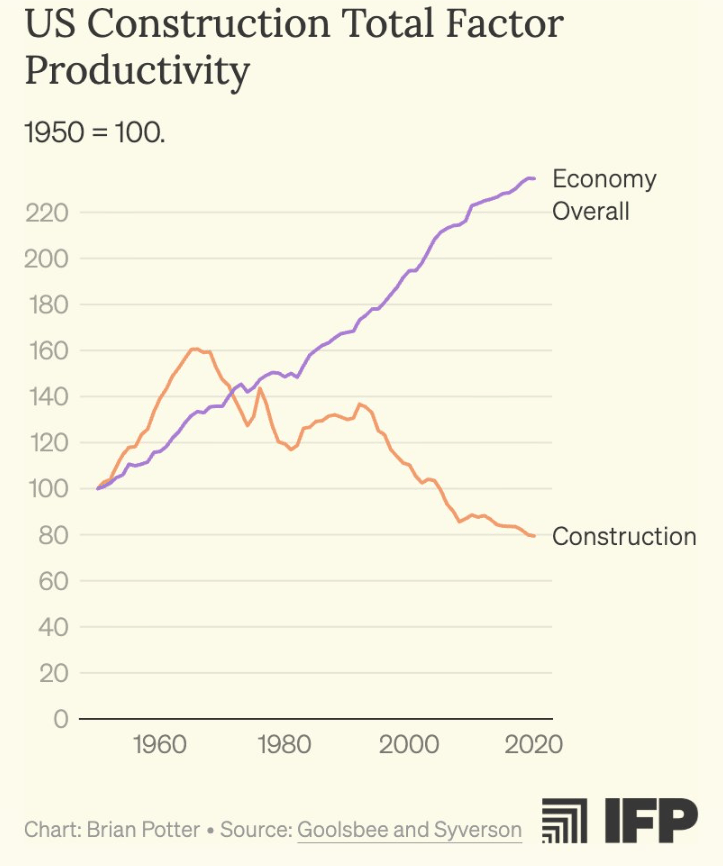

Why houses are expensive:

Houses have gotten so unaffordable in part because construction has missed out on the productivity boom (likely because of things like zoning laws and slow approval processes).

More construction workers would help:

Pay differentials suggest human capital needs to be re-allocated to the construction industry.

Robots make humans more productive:

Economist Jostein Hauge notes that the addition of two million robots to China’s workforce does not seem to have displaced any humans from their jobs.

Record margins:

The valuation guru Aswath Damadaran notes that corporate profitability for the S&P 500 is at an all-time high, thanks to the increasing share of technology companies in the index. He warns, however, that AI could prove to be a “slow motion car wreck” for profit margins in tech.

There’s life beyond tech:

I take the booming share price of Comfort Systems as a signal that the US economy should reallocate capital away from things like banking and software and into things like HVAC systems.

If some of that is human capital, we’ll probably all be better off.

Have a great weekend, correctly allocated readers.

Brought to you by:

US Treasuries are the lifeblood of our financial system, providing collateral to support transactions, but outdated legacy systems hinder collateral mobility.

A new white paper from the ValueExchange dives into the future of collateral mobility, RWA tokenization, and what we can learn from a recent series of on-chain repo transactions conducted on Canton, the only public blockchain built for institutional finance.

With over $8T tokenized transactions flowing on Canton every month, including over $350B of on-chain US Treasuries moving daily, Canton is building the scalable, always-on capital markets infrastructure of the future.

DAS NYC's lineup is bringing the biggest names in finance to the stage.

Don't miss the institutional gathering of the year — this March 24−26.