- The Breakdown

- Posts

- 🟪 Hard money is bad money

🟪 Hard money is bad money

(but a good asset)

Hard money is bad money (but a good asset)

Historians date the start of globalization with surprising precision: June 24, 1571 — the day Manila was founded as the capital of the Spanish East Indies.

There was trade between continents before then, of course. But it was only with the founding of Manila that “a regular and lasting maritime connection established between the four great continents,” according to a history instructively subtitled The Origin of World Trade in 1571.

The new Spanish outpost became the hub of world trade because of Manila’s “fortuitous location at the intersection of two economic systems,” Kenneth Maxwell explains: “The Chinese zone where silver was expensive and the Americas where silver was cheap.”

Silver was expensive in China because it had gradually become the primary medium of exchange there.

Silver was cheap in the Americas because Spanish conquistadors had recently discovered a mountain in the Bolivian Andes seemingly made of silver: Potosí.

Within a few decades, Potosí was producing as much as 80% of the world’s supply of silver, much of which flowed into China.

In return, China provided Europeans with luxury goods like silk, porcelain, textiles and even Christian devotional objects (China was better at making virtually everything other than weaponry at the time).

In 1580, the Ming Dynasty supercharged these trade flows by declaring that all taxes would have to be paid in silver.

A quarter of the world’s population lived in China at the time, and the Ming Dynasty collected taxes from millions of subjects across a sprawling Empire — by far the largest tax regime in the world.

So, choosing to collect those taxes in a metal it produced very little of had consequences for the entire world.

Before then, Chinese farmers typically paid their taxes with the wheat or rice they grew, depending on the season (and nearly all taxpayers were farmers).

To pay taxes thereafter, they had to sell their wheat or rice to someone who had silver, nearly all of which came from abroad (either the Americas or Japan).

Soon, silver was worth twice as much in China as it was in Europe.

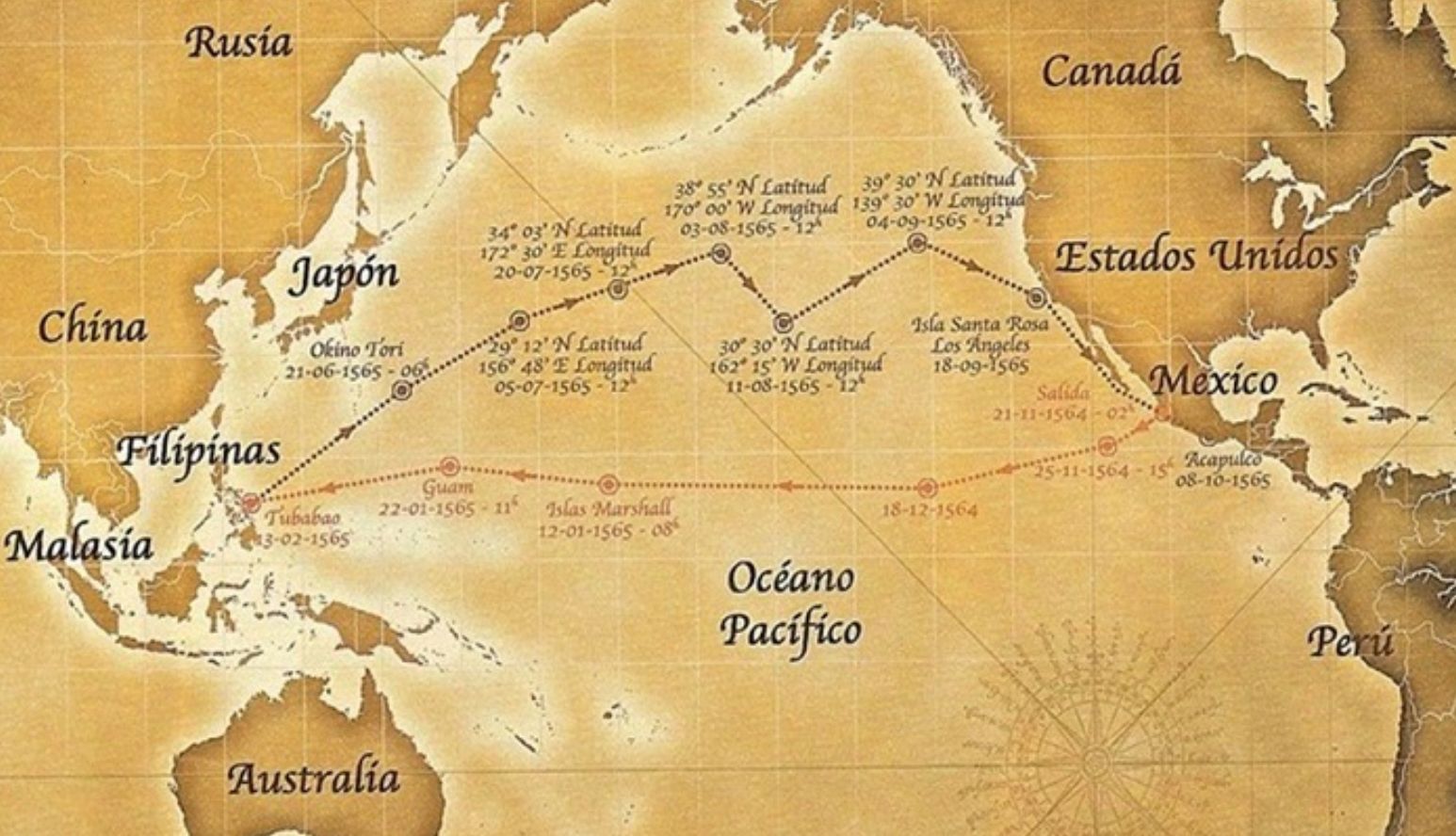

It took a long time for this price discrepancy to be arbitraged away: The roundtrip for the Spanish galleons that carried silver from Acapulco to Manila took nearly a year.

It was also treacherous: As much as 15% of the journeys are thought to have ended in shipwreck, with disease and starvation raising the casualty rate among crews to as high as 50%.

Still, in their enthusiasm to profit from the China/Europe arbitrage, Spanish sailors eventually overdid it: By the end of the 16th century, China was flooded with silver, causing an inflationary shock to the world’s largest economy.

In the 1630s, however, both Spain and Japan restricted silver exports to China, causing a deflationary shock for the Chinese economy and a revenue shock for tax collectors.

When silver became scarce, China’s farmers simply couldn’t pay.

This external supply shock contributed to the fall of the Ming Dynasty in 1644, just 64 years after it required that taxes be paid in money that could only be attained from abroad.

Such are the dangers of outsourcing your monetary policy.

A new history of colonial America argues that British rule fell for the same reason.

In Money and the Making of the American Revolution, Andrew David Edwards explains that the reason colonists hated British taxes so much is not because they were high (they weren’t), but because they had to be paid in silver.

Few colonists could because silver coins like Spanish pieces of eight were constantly flowing out of the colonies. American farmers could barter for goods with their neighbors, but the ships carrying finished goods from Britain accepted only hard money as payment.

That left the locals with little or nothing to pay their taxes.

No less of an observer than Thomas Paine cites this as a primary cause of colonial resistance: “There are two distinct things which make the payment of taxes difficult; the one is the large and real value of the sum to be paid, and the other is the scarcity of the thing in which the payment is to be made.”

The lesson from both Ming China and the British colonies, then, is that hard money is 1) wildly unpopular with taxpayers and 2) existentially dangerous for tax collectors.

In other words: Hard money usually proves to be bad money.

The alternative can be pretty bad as well, of course.

China adopted hard money only after it had caused a hyperinflation by issuing too much paper money (which it invented); and the fiat money the colonies printed to fight the Revolutionary War was similarly inflated away to nothing.

Perhaps as a result, China kept its currency pegged to silver until 1935 and the US didn’t fully abandon gold until 1971.

In both cases, this was a decision forced upon them by events.

But subsequent events have reinforced the hard-earned lesson that, to control their own destiny, governments have to issue their own money.

Most recently, the government of China has been enthused about metallic money again — using the dollars it imports to buy gold because it doesn’t fully trust money that’s issued by a geopolitical rival.

But that, too, highlights the dangers of relying on metallic money. China’s buying has helped push the price of gold up nearly 50% year to date, which would have caused a Ming-like deflationary shock in any country that still demanded it for taxes.

Of course, gold is also up so much because people are worried about governments issuing too much fiat.

That doesn’t make it good money.

But it does make it a good asset.

Brought to you by:

Grayscale is excited to announce the launch of Grayscale CoinDesk Crypto 5 ETF (ticker: GDLC) — the first crypto exchange-traded product in the U.S offering investors access to the market cap-weighted performance of the five largest and most liquid crypto assets1 , covering 90% of the crypto market’s capitalization2 .

Grayscale CoinDesk Crypto 5 ETF (“GDLC” or the “Fund”), an exchange traded product, is not registered under the Investment Company Act of 1940 (or the ’40 Act) and therefore is not subject to the same regulations and protections as 1940 Act registered ETFs and mutual funds. Investing involves risk, including possible loss of principal. An investment in GDLC is subject to a high degree of risk and volatility. GDLC is not suitable for an investor that cannot afford the loss of the entire investment. An investment in the Fund is not a direct investment in any cryptocurrency.

Grayscale CoinDesk Crypto 5 ETF has filed a registration statement (including a prospectus) with the SEC for the offering to which this communication relates. Before you invest, you should read the prospectus in that registration statement and other documents GDLC has filed with the SEC for more complete information about GDLC and this offering. You may get these documents for free by visiting EDGAR on the SEC Web site at www.sec.gov. Alternatively, GDLC or any authorized participant will arrange to send you the prospectus after filing if you request it by calling (833)903-2211 or by contacting Foreside Fund Services, LLC, Three Canal Plaza, Suite 100, Portland, Maine 04101.

Foreside Fund Services, LLC is the Marketing Agent and Grayscale Investments Sponsors, LLC is the sponsor of GDLC.

By Ben Strack |

By Kate Irwin |

By Blockworks |

Sponsored Report |

Brought to you by:

peaq, the Machine Economy Computer, proudly sponsors The Breakdown newsletter. The robots are here — and they’re coming onchain. With peaq, you earn while the robots work.

Recent highlights include: world’s first Machine Economy Free Zone in the UAE, world’s first tokenized robo-farm in Hong Kong, world’s first Web3 Robotics SDK, world’s first onchain robot.

New peaq app: Get early access to tokenized robots. Be the world’s first to benefit from the rise of the robots: https://www.peaq.xyz/

Tell your friends, rack up rewards! 🎉

Some market insights are just too good to not share. Use the Breakdown referral program and snag rewards while you’re at it:

1 Grayscale and CoinDesk, as of 8/29/2025. Largest and most liquid assets reflect eligibility for U.S. exchange and custody accessibility and U.S. dollar or U.S. dollar-related trading pairs. Exclusions include stablecoins, memecoins, gas tokens, privacy tokens, wrapped tokens, staked assets, or pegged assets. Largest is defined by circulating supply market capitalization, and most liquid is defined by 90-day median daily valued traded.

2 CoinDesk as of 08/31/2025, based on the crypto market ’s total investable universe.