- The Breakdown

- Posts

- 🟪 Thursday markets

🟪 Thursday markets

Manipulative algorithms, diamond portraits and emoluments

Thursday markets: Manipulative algorithms, diamond portraits and emoluments

This week, New York Attorney General Letitia James threatened to prosecute prediction-market platforms like Kalshi and Polymarket for offering “unlicensed sports wagering.” In the meantime, she warns us to stay away from them: “I urge all New Yorkers to be cautious of these platforms to protect their money.”

This is like warning someone already losing money at low-odds slot machines not to go play even-odds blackjack instead.

Blogger Joe Pompliano’s deep dive on the traditional services most people use to bet on sports show they are far more predatory than what prediction markets provide.

“Sportsbooks aren’t just hoping a small percentage of customers lose enough money to cover all the winners,” Pompliano writes. “[T]hey are investing hundreds of millions of dollars in AI-enabled algorithms to guarantee it.”

Popular betting services like FanDuel, DraftKings and BetMGM collect comprehensive information on their customers, including your date of birth, address, geolocation and social-media profiles. They additionally take note of whether you bet from a phone or a desktop computer, where your payment comes from, how often you check the site, and what time you like to place bets.

All that information goes into the bookies’ algorithms, designed to encourage losing bettors to bet more and ensure that winning bettors bet hardly at all.

The sportsbooks spend over $1 billion a year to make these algorithms ever more predatory, Pompliano says.

Prediction markets, by contrast, are peer-to-peer: Users bet against each other, not the house, so providers like Kalshi and Polymarket have no reason to profile either of us. They don’t care who wins the bet.

In the US, they collect Know You Customer (KYC) information, but only because the government makes them.

You’ll probably still lose money. But it won’t be because an algorithm identified you as a loser.

One guaranteed loser in prediction markets, however, is the state.

New York, the largest sports-betting market in the US, taxes online-gambling revenue at 51%. In 2025, that generated over $1 billion in tax revenue for the state.

Sports betting on prediction markets, categorized as “event contracts,” generates exactly $0.

I suspect the state might be more worried about the cut they get than the odds you win.

David Canellis misses the “acquisition privacy” that crypto once provided: “The crypto space has lost something incredibly powerful in its evolution out of the self-mining age: the ability for regular users to onboard themselves into crypto through mining.”

Self-mining meant self-onboarding, which used to be the norm. Now, by contrast, nearly everyone gets into crypto by sending fiat from a KYC’d bank account to a KYC’d exchange.

The result? Even the most cypherpunk privacy coin of today is not as private as a goofy-dog coin was a decade ago: “The dogecoins earned by dogecoin miners with GPUs in their garages in 2015 are inherently much more private than Zcash bought on Coinbase,” Canellis says.

You can’t mine crypto in your garage anymore, and that undermines its original purpose: “If crypto is a revolution,” Canellis laments, “it’s one where the entryways are precisely monitored.”

It’s true that crypto has felt a little more revolutionary recently, thanks to its renewed enthusiasm for privacy. Measured by price, at least, Zcash was one of crypto’s few big winners last year.

But Andrew Bailey, co-author of Resistance Money, thinks this is more hype than substance: “If the pump in Zcash was being driven by demand for privacy,” he tells Canellis, “shielded transactions would be up.”

They’re not. Per Blockworks data, shielded transactions (the ones made with Zcash’s opt-in privacy features) have barely changed:

In other words, people aren’t using privacy; they’re only buying the idea of it.

This, Bailey thinks, makes Zcash “fundamentally a memecoin.”

But not all is lost!

Bailey is more hopeful about another OG privacy coin, Monero. Partly because the hardware required to mine it is still cheap enough that you can do it from your garage. This preserves the “acquisition privacy” that’s no longer possible with bitcoin or ether.

And partly because it really is preserving privacy.

Monero, Bailey says, “has crazy users who use [it] to buy drugs, and guns, and prostitutes online, and whatever. That’s Monero.”

And that is how you know you’re not reading The New York Times: He meant all of that as a compliment.

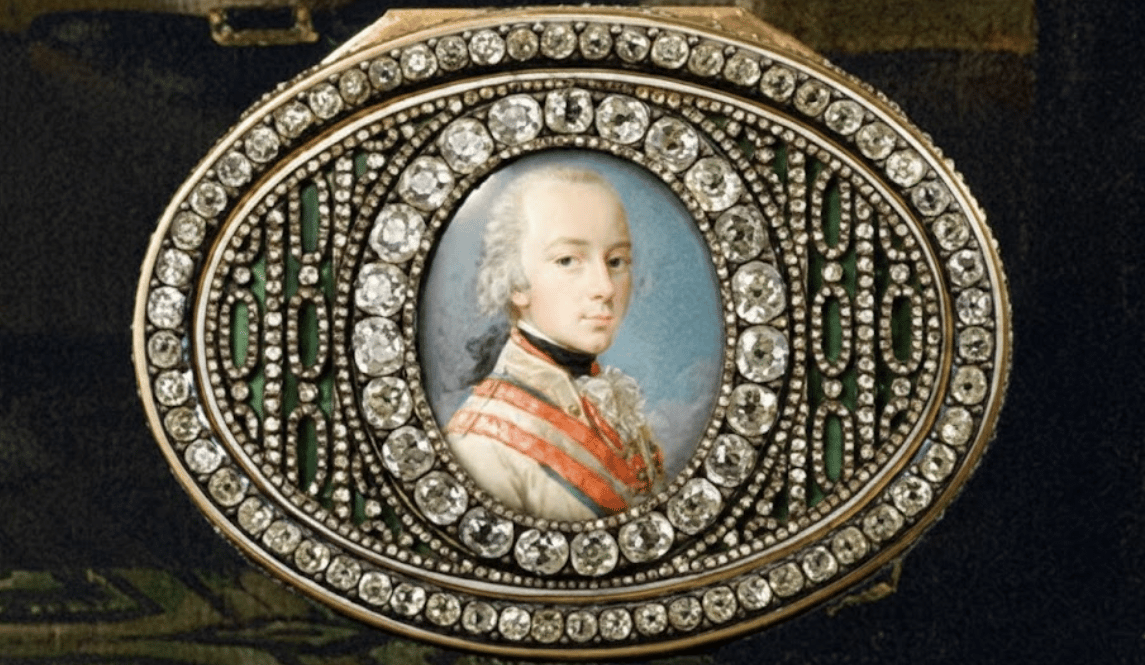

Benjamin Franklin, being a particular favorite of King Louis XVI, received a particularly lavish gift when he left the King’s court in 1785: a boîte à portrait featuring the King’s visage surrounded by 408 diamonds “of a beautiful Water” (meaning unusual clarity).

This was standard procedure in pre-Revolutionary France — departing diplomats customarily received a gift from the King, although not typically a diamond-encrusted one of such magnificence.

But the purpose of post-Revolutionary America was to be meritocratic, not monarchical.

So, upon his return to the newly united states of America, Franklin asked his fellow founding fathers what he should do with his portrait box.

In her paper “Gifts, Offices, and Corruption,” legal professor Zephyr Teachout recounts how the ensuing debate led to an Emoluments Clause of the US Constitution.

“A box was presented to our ambassador by the king of our allies,” Governor Randolph said in explaining the Foreign Emoluments Clause. “It was thought proper, in order to exclude corruption and foreign influence, to prohibit any one in office from receiving or holding any emoluments from foreign states.”

The wording they settled on seems pretty clear: “No Person holding any Office of Profit or Trust under them, shall, without the Consent of the Congress, accept of any present, Emolument, Office, or Title, of any kind whatever, from any King, Prince, or foreign State.”

“Emolument” is generally defined as any form of profit, advantage, benefit or compensation tied to holding public office.

In the nineteenth century, several presidents notified Congress of presents they had received from foreign gift-givers, and either handed them over to Congress or obtained consent for their acceptance.

Other Presidents treated the presents they received as gifts to the United States.

When the King of Siam presented President Lincoln with “a sw[o]rd of costly materials and exquisite workmanship” and two large elephant tusks, Lincoln handed them over to the Department of State. “Our laws forbid the President from receiving these rich presents as personal treasures,” Lincoln informed King Rama. “They are therefore accepted…as tokens of your goodwill and friendship for the American people.”

In 1966, Congress additionally enacted the Foreign Gifts and Decorations Act, which requires congressional consent for federal employees to accept foreign gifts worth more than $480.

So, in 2026, does a $500 million “investment” in a vaporware crypto project constitute a gift or emolument?

I’m not a legal scholar, so I can’t say.

But I’d probably run it by Congress.

Crypto’s premier institutional conference is back this March 24–26 in NYC.

Don’t miss SEC Chairman Paul S. Atkins’ keynote on Day 1.